The “Window Method” for Vines: How to Save a Tree Without Doing Anything Dumb (Like Yanking Vines From 30 Feet Up)

You know that tree in your yard that looks like it’s wearing a vine sweater? The one you’ve been politely ignoring because, technically, it’s “green,” so it feels… fine?

Yeah. It’s not fine.

When vines take over a tree, they don’t just make it look a little haunted. They slowly bully it: stealing light, adding weight, holding moisture against the bark, and if the vines get thick enough literally squeezing the life lines under the bark.

And the worst part is you usually don’t notice until the canopy starts thinning and you’re like, “Huh. Why does my oak look… tired?”

The good news: you can help a tree a lot in one weekend, without climbing anything or ripping bark off like you’re starting a very specific kind of yard war.

The trick is what arborists often call the Window Method. You cut a “window” out of the vine connection so the vine dies up top… while you keep both your tree and your limbs intact.

Let’s do this.

First: How vines actually mess up trees (aka: the slow, leafy heist)

A big vine infestation hits a tree from multiple angles:

- It shades the canopy. Less light = less energy for the tree.

- It adds weight. Wind + ice + a vine blanket = snapped branches.

- It traps moisture against bark. Hello, rot and fungal issues.

- Thick vines can “girdle” the trunk (squeeze the tissue that moves sugars around). That’s the slow strangulation part. Very rude.

If you’re looking up and more than about a quarter of the crown is tangled in vine, or you’re seeing dead branches up high, I’d stop “thinking about it” and start cutting. (This is me lovingly pushing you off the fence.)

What are you dealing with? (Invasive vs. “leave it alone” vs. poison ivy)

Not all vines are the villain. Some are native and useful to wildlife. Others are invasive and will absolutely take your yard hostage.

The “please remove” invasives (common culprits)

- English ivy: evergreen, lobed leaves (often 3-5 lobes), clings with little hairy rootlets, makes dark berries.

- Wintercreeper: small waxy leaves in opposite pairs along the stem (that opposite pairing is the big tell).

- Porcelainberry: looks a bit like grape but has weirdly pretty berries that can be white/pink/blueish. (Pretty, yes. Still a menace.)

Natives that often get blamed unfairly

- Virginia creeper: five leaflets (count them). Birds love it. It can cling, but it’s not the same nightmare as English ivy.

- Native grape: tends to have curled tendrils and that classic grapey look. Can get heavy, but it’s not automatically a “cut it all down” situation.

- Greenbrier: thorny and annoying (it chooses violence), but usually not a mature tree killer.

Poison ivy: different plan, different energy

If you see three leaflets and hairy looking rootlets on the stem… pause. Poison ivy is not a “tough it out” plant. The oil (urushiol) can mess up your week, and it stays potent on dead vines, tools, gloves, and clothing.

And if poison ivy is tangled up with other vines and you can’t tell what you’re touching? Personally, I don’t play botanist Jenga with that. I either gear up like I’m handling toxic waste or I call for backup.

The best time to do this (but also: don’t let timing stop you)

Easiest season? Late fall through early spring.

- You can actually see the vines without all the leaves.

- You’re already in long sleeves.

- Poison ivy is less “active” (still dangerous, just not lush and leafy).

But here’s the thing: if the tree is clearly struggling heavy vine cover, sagging limbs, dieback cut the vines now. The calendar isn’t the boss of you.

Poison ivy safety (read this like your skin depends on it… because it does)

If you’re dealing with poison ivy:

- Wear waterproof gloves (not knit garden gloves those are basically urushiol sponges).

- Long sleeves, long pants, tape wrists and ankles (those gaps are where the oil loves to sneak in).

- Closed toe shoes + eye protection.

- Bag the cut pieces immediately. Double bag and put in the trash (follow your local rules).

Afterward:

- Don’t touch the outside of your gloves/clothes with bare skin while undressing.

- Wash skin ASAP with a poison ivy cleanser (like Tecnu/Zanfel) if you have it.

- Wash clothes separately.

Never, ever burn poison ivy. The oil can get in the smoke and cause a serious airway reaction. That’s not a “tough it out” scenario. That’s a hospital scenario.

Okay. Deep breath. Now the actual method.

The Window Method (the part where you save the tree)

Here’s the whole concept: you’re going to cut the vine in two places creating a gap (“window”) so the vine can’t move water/sugars between roots and leaves. The top dies in place. You do not pull it down like you’re wrestling a garden anaconda.

What you need

- Hand pruners (small stuff)

- Loppers (medium stuff)

- Hand pruning saw (big stuff)

If the vine is thick enough that you’re straining, wobbling, or considering a chainsaw while standing in leaf litter… that’s your sign to call an arborist. I like DIY. I also like people keeping their fingers.

Step 1: Cut your “window” (two cuts, all the way around)

Make two complete cut lines on the trunk:

- Bottom cut: at ground level, cut every vine stem you can find around the base.

- Upper cut: about 4-6 feet up (somewhere between shoulder and head height), cut every vine stem again.

The order doesn’t matter. What matters is that every vine connection between those two points gets severed.

For thick vines: saw slowly and carefully, and don’t pry. If a vine is basically fused to the bark, leave the stuck part. Dead vine attached to bark is way less damaging than you accidentally peeling the tree like a banana.

Step 2: Clear the base (without going full Hulk)

Once the trunk cuts are done, clear vines in a ring around the base roughly 2 feet out.

Best time: after a rain, when the soil is softer.

Pull low vines with steady pressure. If the roots won’t budge, don’t yank until something snaps underground (because that “something” will be your patience and possibly your back). Come back after wetter weather.

Also: old vine root clumps can be shockingly heavy. The first time I pulled one out, I was deeply offended by how much it weighed, like it was personally insulting my arm strength.

Step 3: Do NOT pull the top vines down (this is where people get hurt)

I know it’s tempting. You want the “after” photo today. But dragging vines out of the canopy can:

- tear bark off the trunk,

- snap branches,

- drop dead wood on your head.

Once you’ve cut the window, the vine up top is already dying. It’ll brown out, turn brittle, and over time it’ll fall apart on its own. Let gravity do the dangerous work.

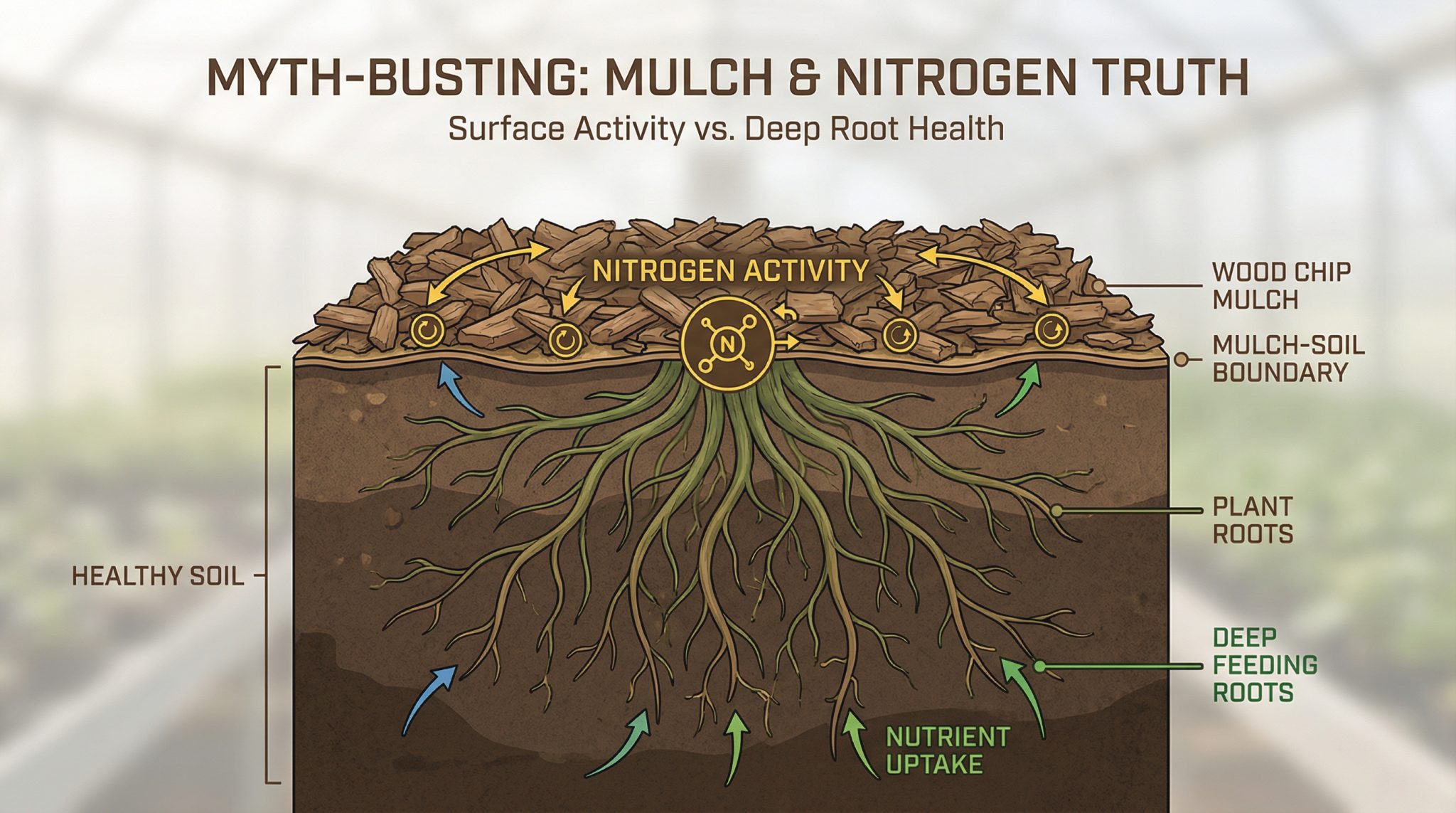

Step 4: Mulch like you mean it

After you clear the base, mulch the area to suppress regrowth:

- Spread about 2 inches of wood chips or leaf mulch in about a 3 foot radius.

- Keep mulch a few inches away from the trunk (no mulch volcanoes trees hate that).

Mulch helps, but it’s not magic. Which leads us to…

“It’s coming back.” Yep. Here’s what to do.

Vines are persistent after repeated cuts. (Honestly, I’d respect their work ethic if they weren’t ruining trees.)

Your easiest follow up plan

- First 6 weeks: check for new shoots around the base.

- Through the first growing season: cut any new shoots at ground level whenever you spot them.

- Year 2-3: check a couple times each spring/summer. Regrowth should get weaker if you stay on it.

Each time you cut new growth, the plant spends energy it can’t fully replace. Think of it like making the vine pay rent until it goes broke.

Optional: herbicide (only if you’re careful and only at the base)

Sometimes, especially with stubborn invasives (looking at you, English ivy), you’ll get regrowth no matter how smug you feel after cutting.

Herbicide can help if:

- you can apply it at ground level to cut stems,

- you can avoid getting it on tree bark or surrounding plants,

- you are NOT spraying overhead (don’t do that).

The most effective approach is usually cut stump treatment:

- Re-cut the stem at ground level.

- Within about 15 minutes, paint herbicide directly onto the fresh cut with a small brush (not a sprayer).

- Use chemical resistant gloves and follow the product label exactly.

Common active ingredients used for woody vines when removing wild grape are triclopyr or glyphosate in concentrate form labeled for cut stump use. (And skip the “ready to use” diluted sprays for this woody roots tend to laugh at them.)

Also: don’t apply in extreme heat, and don’t apply if rain is imminent (follow the label’s rainfast window).

If you don’t want to use herbicide at all, you can still win you’ll just be relying more on repeat cutting and patience.

Signs you’re winning (because you deserve a little hope)

- Within a month, the vine above your upper cut starts browning and looking crispy.

- By the end of the season, the canopy looks less choked and more “tree,” less “vine monster.”

- Over a year or two, dead vine sections start dropping out naturally.

And the tree? Trees are surprisingly resilient once they can breathe again.

When I’d call an arborist (no shame, just wisdom)

Call an ISA certified arborist if:

- vine stems at the base are over ~3 inches thick,

- vines cover more than half the crown,

- anything is near power lines,

- the trunk/major limbs are fully wrapped,

- poison ivy would require cutting above head height.

This isn’t about being “bad at DIY.” This is about not getting crushed by a falling limb because you wanted to save money on a Saturday.

If you do one thing this weekend…

Pick the worst vine wrapped tree and do the Window Method cuts: ground level + 4-6 feet up, all the way around.

That one step alone is a huge relief for the tree and it’s the difference between “my yard has some vines” and “my trees are being slowly assassinated.”

Go make your little vine “window.” Your tree will thank you. And you’ll get to walk past it feeling mildly heroic, which is honestly one of my favorite homeownership perks.